The following mobility and balance test material is taken from draft manuscript excerpts of my book Ageless Balance.

“If you can’t measure it, you can’t improve it.”– Peter Drucker

Many people only realize the extent of their mobility loss once it significantly impacts their daily lives. Lucky for us, we have the capacity to notice subtle signs that our capacity to do balance is changing. The first symptoms of loss of mobility are changes in how we move from sitting to standing and how we walk. Because these changes can be debilitating and impact our level of independence, it’s crucial to self-assess our mobility often.

The following mobility and balance tests are convenient, easy to do and standard in the healthcare industry. You can complete the tests wearing shoes or, for some who want an extra challenge, in your bare feet (no socks). When we wear shoes, the nervous system interprets the shoe as a larger Base of Support. Be sure to make a note, “Shoes On” or “Shoes Off,” so you can repeat the tests with consistency. You need a stopwatch or a timer; both are readily available on your mobile phone. Or ask a family member or friend to assist. Some balance tests are timed, while others merely attempt to introduce you to observing and tracking fundamental movement patterns.

What to do:

- Read the description of the test.

- Give yourself two practice trials.

- After the practice, perform the test. When the test is timed, take an average of the three trials.

- Record your findings and your perceived Balance Confidence* in your phone’s calendar or note section so that you can track your progress.

- Remember, to the best of your ability, relax and refrain from holding your breath and straining.

*Balance Confidence Rating Scale

| Confidence Level | Score Range | Description |

| Low Level of Confidence | 0 | “I can’t do that at all. In fact, it scares me, and I literally freeze. I can’t move.” |

| Low Level of Confidence | 10 – 20 – 30 | “I am scared I’m going to fall. I will try to move, but only if I have the help of another or the support of an assistive device, the wall, or furniture to hang on to. I feel like I have to grip really hard to hold on and balance.” |

| Moderate Level of Confidence | 40 – 50 – 60 | “I feel myself wobble and sway, and that makes me feel cautious and a little slow in my movements. Occasionally, my foot or hand must touch something to feel more secure or steady. But I can keep trying and move differently from what I am used to.” |

| High Level of Confidence | 70 – 80 – 90 | “I feel a sense of strength, and I notice the wobble or sway at times. Overall, I feel connected and coordinated and can move with some speed. I wonder to myself, ‘Is this what agility feels like? Is this what ageless balance could feel like?’ I occasionally have the urge to lower my foot or hand and use it to steady myself, but I rarely need to. If I do use my foot or hand, I don’t judge myself harshly.” |

| Highest Level of Confidence | 100 | “I just did that move without even thinking about balancing, falling, or feeling any restrictions anywhere. Boom! I just did it.” |

-Words of Wisdom from Kim R.

Instead of fixating on the number of seconds, I’ve started to view my progress in a different light. I’ve stopped categorizing my performance as good or bad. I’ve become adept at identifying negative self-talk. I can now recognize the quality of my foot imprint as I stand. This recognition has empowered me to cue myself differently: How can I stand a little taller and feel myself pressing into the ground? How can my foot be a little longer or feel a little wider? This, I believe, is how I progress along the ‘Balance Confidence Scale’. And as an added bonus, my steps and seconds are now improving too!

The following three assessments provide a baseline and help you differentiate what you are already doing well and where you need to direct your attention.

30 Second Sit-to-Stand Test (STS)

This test is a general measure of leg strength, balance, fall risk, and exercise capacity requiring you to repeatedly stand up from a seated position from a solid chair (no wheels and approximately 17-inch height) and sit back down. Equally important, it allows a person to examine patterns of overuse or poor habits that may have been necessary at one time but are no longer needed. For example, you may be unaware that you use one or both hands to push yourself up to stand, or you may favor one leg over the other when trying to stand up.

This is one test you want to repeat often and track changes over time. Observe not only improvement in numbers but also recognize that progress is also measured in noting less assistance from your hands or leaning into one leg.

- Place a chair, preferably with no arms, with its back against a wall or door. Sit upright in the middle of the chair, arms resting on chest, crossed at the wrists, feet approximately shoulder-width apart, and placed on the floor at an angle slightly back from the knees. If needed, adjust one foot slightly in front of the other to help maintain balance when standing. To stand, push through the heels and keep your knees in line with your toes.

- Count the number of times you complete full stands in 30 seconds, without using your arms, and without plopping on the return. If you must use one or both hands, do so and note the effort, a lot or minimal. Also note and record if you favor or lean more into one leg versus the other.

- Record the number and your Balance Confidence.*

What’s normal:

Want another level of challenge? Try one of these variations or combine several. Understand that they are not a part of the original test but offer another level of challenge to the sensory systems that shape the balance neural pathways in the brain.

- Keep your eyes closed throughout the whole test. Record the number of sit-to-stands and note that your eyes were closed.

- Change the speed of your sit-to-stand:

- Super s-l-o-w

- A combination of slow and fast

- Stand UP FAST, sit DOWN SLOW

- Stand UP SLOW, sit DOWN FAST

- Change the position of your arms:

- Hands on top of the pelvic bone (waist level – take a super hero pose)

- Arms by your side

- Arms out in front of you

- Change the position of your feet: use your arms in any way necessary to maintain your balance:

- Split stance, even weighted

- Split stance, place more weight on the back foot

- Tandem stance (the toes of one foot touching the back of the other foot)

- Place a small ball or couch pillow between the knees

- Hold hand dumbbells:

- Near the chest

- Arms by your side

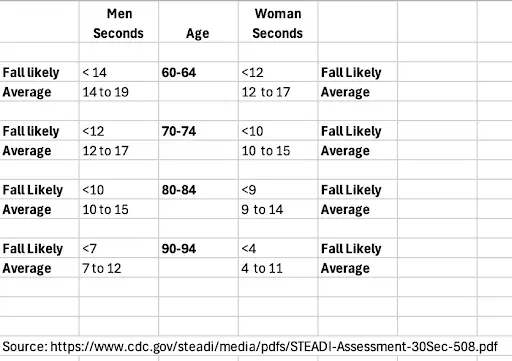

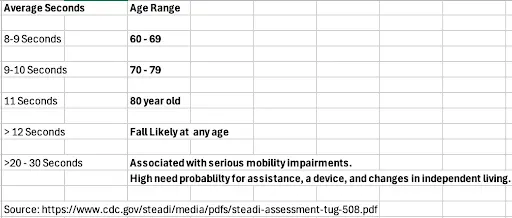

Gait Speed as the 6th vital sign: Timed Up and Go Test (TUG)

With each visit to a healthcare facility, there is the predictable vital sign assessment. These tests measure your overall physical health and monitor for medical problems: Body temperature, pulse and respiration rate, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation. And yet, rarely are we asked to demonstrate how fast we can walk and turn, two movement qualities that indicate fall risk and accurately assess the ability of your nervous system to “do balance.” It is well-documented that slow walking speeds: <1.0 m/s (2.25 mph) are associated with frailty and 1-1.3m/s (2.9 mph) are associated with falls. Your capacity for ageless balance can change over the years. The question you want to ask yourself is: “Is it acceptable for me to become slower, stooped and more sedentary because I am older?”

The TUG test is a simple but powerful way to measure your level of physical function, including speed and turning. As you record the number of seconds it took to complete the test, note how you turned to return to your seat. Did you turn to the right or left? Also, record if you used any assistive device, such as a cane, walking stick, crutch, or walker.

- Place a chair, without arms, near a wall or door. Measure out from the chair 3 meters (about 10 feet) and place a marker on the floor, e.g., a piece of tape.

- Measure the time it takes to stand up from a standard chair, walk at your normal pace to the marker (three meters or 10 feet), turn around, come back, and sit down again with your back leaning against the chair.

- Record the number and your Balance Confidence.*

What’s normal: Just because you hit the target zone for your biological age, the question you want to ask yourself is: “Is it acceptable for me to become slower because I am older?”

15-second Step Test (Dynamic Balance)

A minimum level of strength is needed to stand on one leg while the other leg is in the air. However, a high level of coordination and timing (motor control) between the two legs is needed to complete this next test successfully. This test also correlates well with leg strength, walking speed, and balance.

- Stand upright without holding on to any device, wall, or person, and with both feet facing a step.

- Place one foot flat onto a 7.5cm (about 3 inches) high step, then bring the foot back to the floor. Do this repeatedly, as quickly and safely as possible, counting the total number of times you can do this in 15 seconds.

- Record the number and your Balance Confidence.*

- Repeat the balance test on the other side and record the number and your Balance Confidence.*

What’s normal:

- 20 steps in 15 seconds

- <12 puts you in the fall risk category

A special comment worth noting. If you had to lean or touch the wall, chair or countertop, it doesn’t mean you failed. It means that currently your nervous system needs a larger base of support to feel safe enough to repeatedly and rapidly lift the foot from the ground.

Ageless Balance Tip: Practice makes progress, not perfection!

Remember, the purpose of every balance test is simple. These tests give you feedback or increase your awareness of where you are starting from. You are establishing your GPS location. Allow yourself some grace. If the challenge of narrowing the width between the two feet is scary, overwhelming, or “not doable,” then increase the distance between the two feet. Or maybe you need to hold on to the countertop or lightly touch the wall at first. That’s okay. You are okay! Record that as assistance. This is your personal starting point. It doesn’t mean that you have failed.

Success is defined as progress, not perfection!

How well are we aging? It’s an important question that we can start to answer. These three simple balance tests are designed to reveal key factors influencing your ability to do balance: muscle strength, joint health, pain and the crucial role your nervous system plays in coordinating movement. The results of these tests closely predict your risk of falling, your long-term health outcomes, and your future independence. So, take the time to properly assess yourself and get an accurate measure to track your progress.

Chapter Sources:

Jia S, Si Y, Guo C, Wang P, Li S, Wang J, Wang X. The prediction model of fall risk for the elderly based on gait analysis. BMC Public Health. 2024 Aug 13;24(1):2206. https://doi: 10.1186/s12889-024-19760-8. PMID: 39138430; PMCID: PMC11323353

https://www.cdc.gov/steadi/media/pdfs/STEADI-Assessment-30Sec-508.pdf

An increase in STS repetitions was associated with fewer falls indicating that motor performance is important to consider when screening for fall risk. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0176946

Comprehensive Assessment of Lower Limb Function and Muscle Strength in Sarcopenia: Insights from the Sit-to-Stand Test Ann Geriatr Med Res. 2024;28(1):1-8. Published online February 8, 2024 https://doi.org/10.4235/agmr.23.0205

Adam CE, Fitzpatrick AL, Leary CS, Hajat A, Ilango SD, Park C, Phelan EA, Semmens EO. Change in gait speed and fall risk among community-dwelling older adults with and without mild cognitive impairment: a retrospective cohort analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2023 May 25;23(1):328. doi: 10.1186/s12877-023-03890-6. PMID: 37231344; PMCID: PMC10214622.

https://www.medbridge.com/blog/timed-up-and-go-test-how-to-perform-and-interpret-results

Dias, J. F., Sampaio, R. F., Borges, P. R. T., Ocarino, J. M., & Resende, R. A. (2024). Timed up and go and 30-S chair-stand tests applied via video call are reliable and provide results similar to face-to-face assessment of older adults with different musculoskeletal conditions. Journal of bodywork and movement therapies, 40, 1072–1078. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39593414/