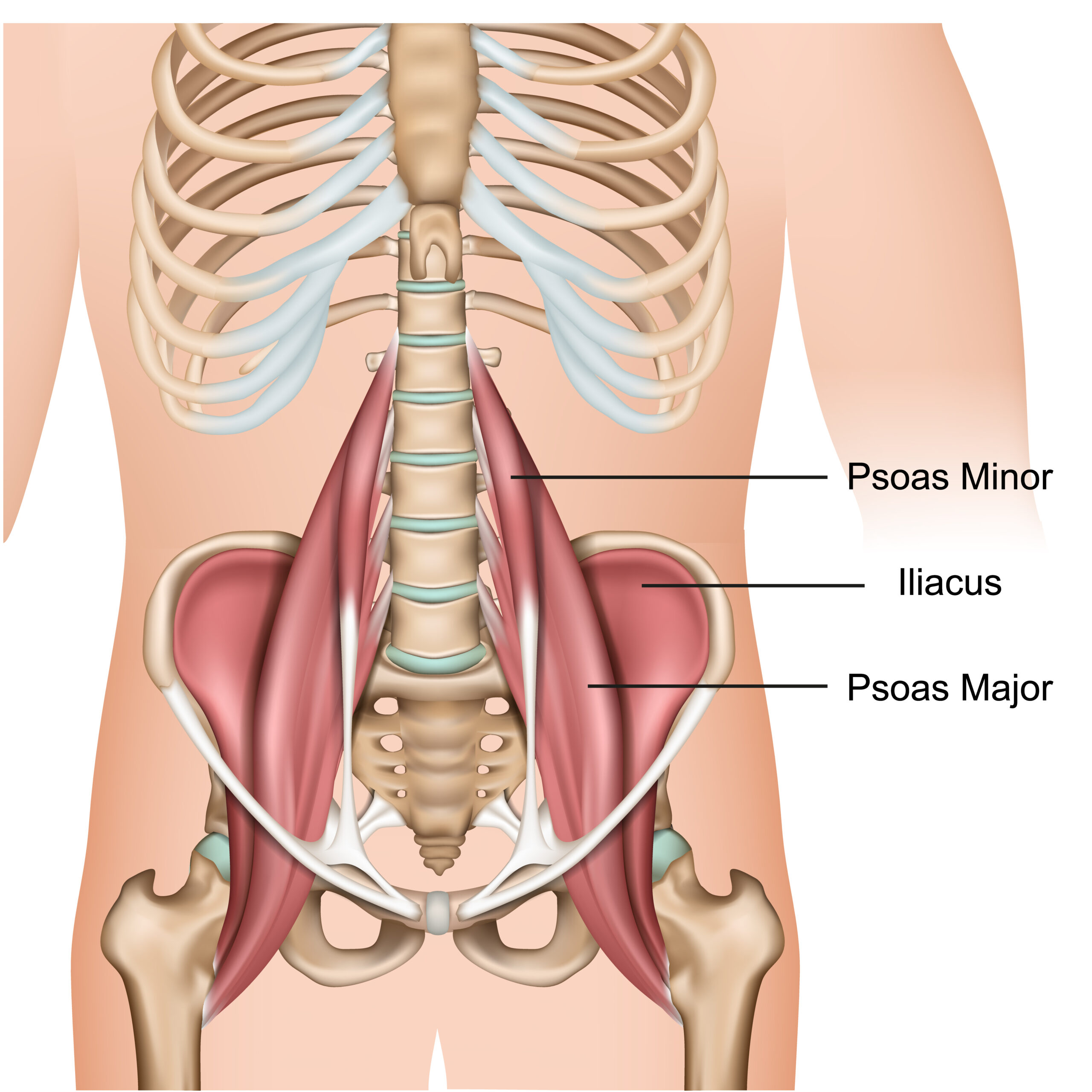

Located in our lower belly, beneath our fat, and under our large and small intestines, lies two muscles that look like suspension bridge cables piercing through our diaphragm (breathing muscle), connecting our lower spine to our femur (thigh bone). The psoas (pronounced so-az) muscles are a part of our deep core muscle groups that markedly influence our spinal alignment, leg movements, and breathing quality. Since it is the only muscle that connects the spine to the legs, everyday actions would be impossible without it. So, why is everyone trying to ‘stretch’ or ‘release’ a tight psoas muscle? Was it your Dr. Google Search that identified this tightness as the source of your problem, or did a healthcare or wellness professional tell you that the pain you experience is due to a tight psoas muscle that needs stretching?

Why You Need To Learn About The Psoas Muscle

There are several reasons why someone would need to learn about the psoas muscle. For example, the psoas muscle is responsible for stabilizing your lower back while you lift your leg at the same time, such as putting on your pants, shoes, and socks or getting out of the car, or climbing steps or a curb — movements we constantly use throughout the day. In addition, athletic competitions in football, basketball, soccer, track, and field need a responsive psoas muscle and its partners for vertical jumping, pushing, and running. People also use the psoas muscle in everyday activities. Walking, lifting, and even sitting down all require the activation of this muscle. These muscles allow us to sustain standing upright for extended periods for cooking, cleaning, and protecting the lower back from overextending.

Therefore, if the psoas muscle is excessively tight, weak, or not functioning correctly during patterns of movement, it can lead to problems with chronic constipation, bladder issues, nerve irritation, balance and posture, chronic back pain, degenerative disc disease, hip and spinal osteoarthritis, hip impingement syndromes, including hip bursitis and tendonitis and even influence osteoporosis of the lumbar spine. When the psoas is not engaged optimally, it is a significant issue for anyone. It affects the quality of alignment and integral relationship of the spine, pelvis, and leg. Over time, the shift in the relationship of your structural alignment, or how your nervous system organizes your head over your pelvis (center of mass) and your feet (base of support), directly contributes to a loss of flexibility, strength, and balance confidence experienced in everyday movement. Monitoring the current position and possible relocation options of the head, COM, and BOS is one of the main jobs of the nervous system, in addition to keeping us upright, moving in any direction, and preventing us from falling.

Reasons for a Tight Psoas Muscle: Read Carefully — Not the Usual Yada, Yada

Most people think that the root cause of body pain is ‘tight muscles that just need stretching’ (or strengthening). It is valid and essential to know that all quality functions depend upon a muscle’s ability to change shape quickly and maintain a proper resting length. But people don’t know or understand that the ‘tightness’ of any muscle is controlled by your nervous system, not the muscle itself. The brain develops movement patterns by coordinating groups of muscles to work together and is behind all the activities we do throughout the day. It does not select, individualize, or target one muscle to become tight or contracted. The nervous system is very efficient and its job is to always protect itself and balance the interactions among all the 30-40 trillion cells in the body, in addition to balancing our head over our pelvis and feet. That is a big job, and it uses its energy and resources effectively.

The brain decides how long or short muscles will be; in other words, which muscles turn on — contracted (facilitated), and which group of muscles turn off — lengthened (inhibited). And the brain bases its decision on the information received from the specialized receptors in your muscles, tendons, joint capsules, fascia, and the visual and vestibular (inner ear) systems. The information received from these primary sensory systems informs the brain in three ways:

- Assess what is happening in the environment, where the Head—Center of Mass (COM or pelvis)—Base of Support (BOS or feet) are in relationship to one another, and what is needed to move this relationship within the environment safely.

- Decide what skeletal ‘parts’ (joints, muscles, and fascia) are available to the nervous system to activate a movement response based on the information received. The nervous system directs which muscles will contract (facilitate). The brain’s decision-making process reflexively or automatically turns off (inhibiting) other muscles.

- Determine to what degree or intensity should the nervous system activate that movement response: speed, force, and coordination (motor control).

A ‘tight’ psoas muscle never exists in isolation. It often represents a more significant dysfunction not only in the musculoskeletal system but in the nervous system as well. — Carol Montgomery

So how does a tight psoas muscle become tight? Or is a better question, what information is the nervous system receiving that results in the brain’s decision to contract the psoas muscle in the first place? Here are four underlying causes of why a muscle is tight:

Protection

If you are continuously trying to stretch, foam roller, or deep tissue massaging a tight muscle, but only to have the muscle pain and tension return, then you are experiencing the power of your nervous system’s primary directive of keeping you and all your body parts as safe as possible. Somewhere along the pathway of the psoas–abdomen, lower spine, pelvis, or upper thigh, the nervous system has received information that movement in any or all the areas threatens the relationship between your Head—COM—BOS. Remember, these three areas are the brain’s top priority, and it wants to stack them up just enough to keep us moving and from falling over! The brain will restrict, stop, or limit movement by signaling a group of muscles to tighten so the head can stack over its best perceived BOS. It is trying to limit movement if it perceives a threat or the probability of a threat. The threat could originate in the external environment, and the nervous system also monitors the possibility of a threat inside us. Specialized receptors throughout our body can sense if an area is pulled apart too quickly or far. An example of this would be almost falling because you twist your ankle stepping off a curb. Unless there is a change in the incoming sensory signals, the brain will not change its outgoing response: tighten the psoas (and other muscles you may not be aware of consciously) to keep the area safe.

Repetitive movements

Recall we accomplish everyday activities because of the nervous system’s ability to simultaneously activate and coordinate specified muscle groups to work together to conserve and efficiently use our body’s energy. When you perform repetitive movement patterns such as sitting or standing for long periods, e.g., regularly participate in activities that require hip flexion (leg lifting) such as kicking, running, or cycling or working out on a recumbent bike); you tip the scales of incoming sensory information to the brain to favor the psoas and other muscles who have a similar action on the skeleton system. This information indirectly leads to the psoas becoming chronically activated because no opposing sensory information is transmitted to the brain. The brain uses current sensory information and past analysis of old sensory information to predict what is needed to move forward. The outcome means turning on specific muscle groups (facilitation) and turning off others (inhibition). Incoming sensory information influences the shortlist of available joints and muscles the brain can activate. In the chronic absence of sensory stimulation of the full range of motion in your joints, your brain has already decided the probability of whether it can use a joint to complete a movement pattern or not.

Trauma

There is a delicate balance and ongoing relationship between nerves that turn on, activate, contract, or facilitate muscles to be short and tight and those that turn off, release, or inhibit muscles from relaxing and elongating. We have more nerve pathways in our body that can facilitate versus inhibit. When you sustain physical trauma to the head or spinal cord, there is a disruption in the relationship balance between the two sets of nerves. The result is tightness or increased muscle tone in specific groups of muscles, namely those that draw the extremities inward (adduction) and bend (flexion) joints, e.g., toe flexion, knee flexion, hip flexion, pelvic rotation, shoulder adduction, and elbow flexion. This excessive muscle tightness takes on a new name called spasticity or spasms. It can feel like mild stiffness to uncontrollable spasms. Head, brain, and spinal cord injuries typically occur from car or motorcycle accidents, falls, and athletic injuries; however, ‘tight psoas muscle’ is also present with autoimmune diseases such as Multiple Sclerosis, Lupus or neurological insults or diseases of the cerebellum, Parkinson’s Disease, Cerebral Palsy, Stroke, and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS).

Change in pelvic alignment

Our pelvis has a peculiar shape, with the sides of the pelvis looking like elephant ears connected in front by a piece of thick cartilage and the back by ligaments binding to the sacrum, the triangle-shaped bone at the end of the spine. However, the interior of the pelvis is shaped like a bowl. There is a delicate balance that occurs to keeping the pelvic bowl moving in all directions and yet level at the same time. When that balance is disturbed due to excessive tipping of the pelvic bowl forward (anterior pelvic tilt), such as pregnancy, being overweight or having an excessive amount of lower abdominal fat, or scarring in the abdomen due to multiple surgeries, the brain will activate the psoas to abort the tilt, trying to protect the joints of the lower back or lumbar spine. Unless the nervous system receives specific information from the foot, ankle, hip, or thoracic spine, it will continue to facilitate or fire the nerves that turn on the psoas to counter the tilt.

Remember, it is not about forcing a movement, pulling apart a muscle, or beating a tight muscle into submission using deep tissue massage, foam rolling, or instrument-assisted soft tissue mobilization. These modalities have their place in the healthcare and wellness toolkit. Still, all too often, there are used unconsciously and reflexively to treat ‘joint stiffness’ and target a ‘tight muscle.’ It is about inputting the needed sensory information to allow the nervous system to make better decisions about which muscle groups need to facilitate to satisfy the nervous system’s primary goals of efficiency and safety. Consciously and selectively changing the incoming information offers us the profound ability to partner in the reorganization of our body.

When we learn that it is the nervous system that is tightening muscles, we learn that we can consciously become influencers of a system that previously we thought was out of our control or that we could only be passive bystanders as we struggle to understand why our body is slowly falling apart, a betrayal on some level, and ‘out to get us.’ Eventually, knowing how the nervous system works transforms into a pearl of wisdom, allowing us to partner respectfully and compassionately our mental thinking with our physical body. We begin to change what we thought could never change. We begin to move in ways we thought we could never move again. We begin to feel the joy that free, spontaneous movement unconsciously renders. We have changed our thinking and ultimately increased our potential to better care for ourselves as we age and move across our lifespan.

In next month’s blog, we will uncover 5 Signs Your Psoas Muscles are Tight and identify a few movement strategies that create lasting, muscle lengthening and better movement patterns for health, vitality, and those basic everyday movement patterns, like walking, climbing stairs, sitting to stand, running, and getting up and down from the floor.

If pain, fear of pain, or chronic tightness persists, don’t ignore your body’s signals and wait until it interferes with your everyday activities, you should seek professional help. You can contact Montgomery Somatics to book an online session so that we can determine the best treatment choice and movement options for you.