In Part 1, we examined how muscles tighten and why a Psoas muscle, located deep beneath your abdominal fat and organs, might be tight. The Psoas (pronounced so-az) muscles are a part of our deep core muscle groups that markedly influence our spinal alignment, leg movements, and breathing quality. Since it is the only muscle that connects the spine to the legs, everyday actions would be impossible without it.

When the Psoas is not engaged optimally, it is a significant issue for anyone. It affects the quality of alignment and integral relationship of the spine, pelvis, and leg. Over time, there is a shift in the relationship of your structural alignment, or how your nervous system organizes your head over your pelvis (center of mass) and your feet (base of support). The shift directly contributes to a loss of flexibility, strength, and balance confidence experienced in everyday movement.

8 Signs Your Psoas Muscles are Tight

- When sitting for long periods, you experience a slow, gradual ache in your lower back, groin, or top of the upper thigh. Or you gradually lose the flexibility in the neck and middle back, finding it difficult to turn and look over your shoulder.

- You must use your hands to help push yourself up to stand up from a seated position. Or, when you go from sitting to standing, you never really come fully erect at the groin, the place where the leg and pelvis meet, which is called the hip joint. The pelvis never entirely comes forward and is chronically held behind the foot, which increases compression on the spinal joints and eventually leads to the ‘walking like an old person’ image.

- When you walk or run, you feel a gradual tightness across your lower back at the waist level or vertically along one side of your lower spine, or your hip feels tight or in a bind, especially as you try to increase your stride length.

- You feel a sharp pain in your lower back, groin, or upper thigh when you bend over to pick something up off the floor. Or you may have difficulty with your balance or pain when raising your foot to tie your shoes or step into pants.

- You have difficulty rotating your legs inward or your foot turns to the side instead of straight ahead—or difficulty performing specific movements, such as a squat or climbing deep steps or steep hills.

- You have a very large abdomen that protrudes past the pubic area of the pelvis. Or you have a very large pannus, which are folds of abdominal skin and fat that hang down past the pubic area of the pelvis and rest on the upper thighs.

- You have an exacerbation of a neurological condition such as a pinched nerve in the Lumbar Spine, Multiple Sclerosis, Parkinson’s Disease, Cerebral Palsy, Brain or Head injury, or Stroke.

- When lying on your back with both knees bent and feet flat on the floor, draw one knee toward your chest and hold it there with your hands clasped around the top of the knee. Slowly slide the foot on the floor away from your pelvis, allowing the knee to straighten fully. Suppose the back of the upper leg or thigh of the extended leg does not touch the ground. In that case, that is a good indication that your psoas muscle is facilitated and cannot lengthen optimally.

How a Position Influences the Nervous System

One of the main jobs of the nervous system is to monitor the current position and possible relocation options of the head, COM (center of mass), and BOS (base of support), in addition to keeping us upright, moving in any direction, and preventing us from falling.

When the Psoas is not engaged optimally, it is a significant issue for anyone. It affects the quality of alignment and integral relationship of the spine, pelvis, and leg. Over time, the shift in the relationship of our structural alignment, or how our nervous system organizes our head over COM and BOS, directly contributes to a loss of flexibility, strength, and balance confidence experienced in everyday movement.

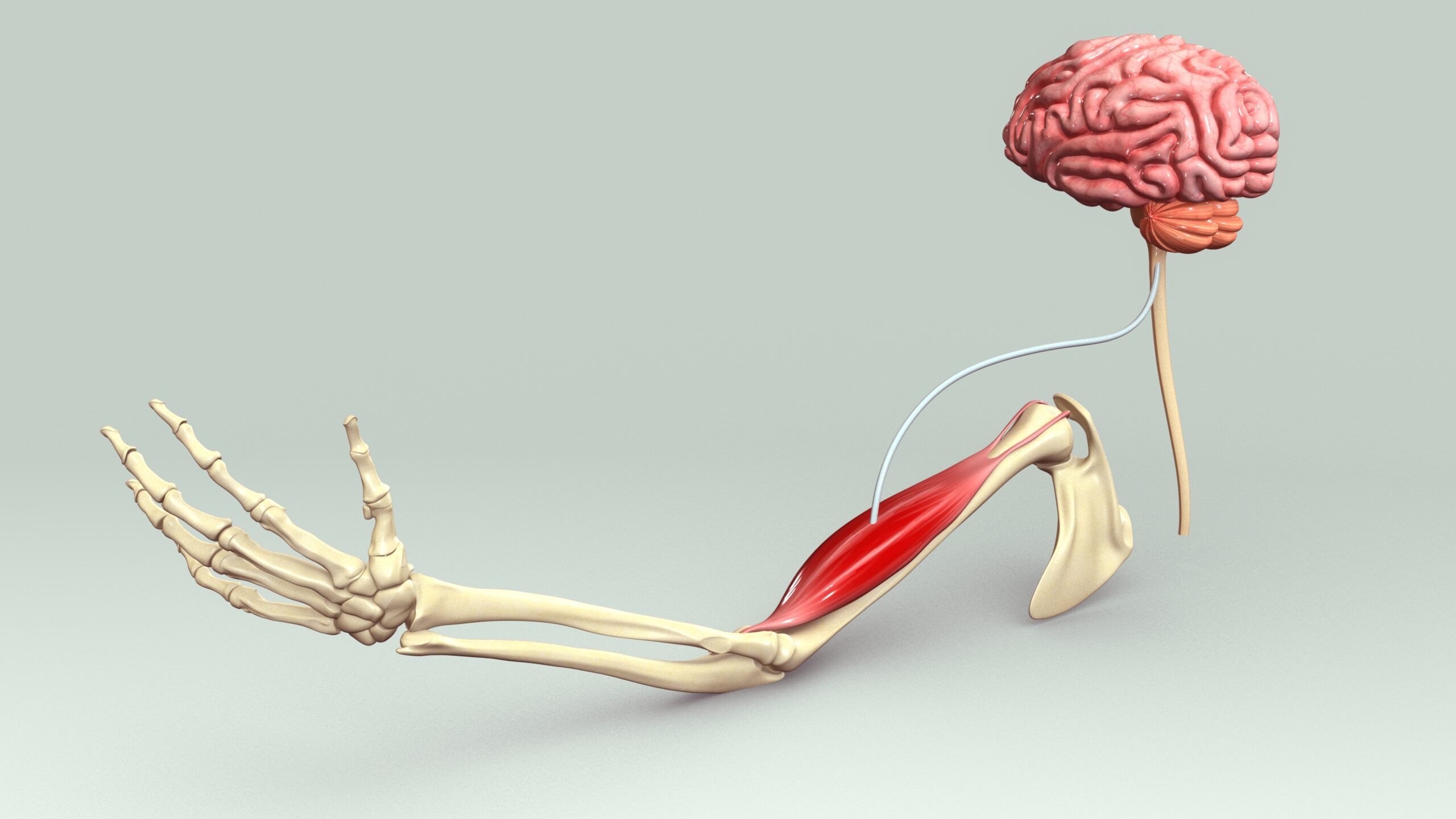

Most people think that the root cause of body pain is ‘tight muscles that just need stretching’ (or strengthening.) But people don’t know or understand that the ‘tightness’ of any muscle is controlled by your nervous system, not the muscle itself.

The brain decides how long or short muscles will be; in other words, which muscles turn on— contracted (facilitated), and which group of muscles turn off—lengthened (inhibited). And the brain bases its decision on the information received from the specialized receptors in your muscles, tendons, joint capsules, fascia, and the visual and vestibular (inner ear) systems.

Awareness in how we move

creates changes in physical alignment

and freedom from unconscious patterns

of facilitated or tight muscles.

– Carol Montgomery

How to Release a Tight Psoas

You will succeed more in ‘lengthening or stretching’ a tight muscle if you start to turn on, facilitate, or activate groups of muscles that reflexively turn off, inhibit, or deactivate the Psoas. Let’s identify a few movement strategies done frequently and with awareness to create lasting muscle lengthening and better movement patterns for health, vitality, and those basic everyday movement patterns, like walking, climbing stairs, sitting to stand, running, and getting up and down from the floor.

Elevator Buttocks:

Sit in a chair with torso erect and supported by the back of the chair. Keep feet flat on the floor, thighs, and knees parallel to each other. Actively contract, squeeze, or pull together your two buttock cheeks (gluteal muscles) as though they could touch or meet in the middle of the chair. Go slow and imagine that the pulling together of the two sides is like an elevator door closing. And then, as you squeeze a little more, and a little more, and a little more, feel your torso and head ascend upward or ‘grow tall’ while the soles of the feet begin to feel a downward pressure into the floor.

Then reverse the movement, slowly releasing the squeeze of the gluteal muscles, sensing how the torso settles back down into the chair seat and the feet release the downward pressure. Notice if you hold your breath while doing the movement at first — it is a very natural response.

Once you have the Elevator Buttocks movement pattern down, add a slow inhale through the nose as large as possible while squeezing the Gluteal muscles. As you reverse the ‘elevator,’ gradually letting go of the squeeze, slowly exhale through the nose. Pause for 15-20 seconds before starting the process again. After sitting for long periods, repeat Elevator Buttocks for 4-5 repetitions before you stand up.

Single Elevator Buttocks:

To improve flexibility in the neck and middle back and allow you to increase the range and quality over your shoulder, repeat the Elevator Buttocks only on one side, the side you want to improve, 4 to 5 repetitions. As you retest your ability to turn the head over the shoulder, allow your middle back to move or glide across the back of the chair.

Center Heel Presses:

This move not only helps you stand up from a seated position without using your hands, but it also allows you to experience what it is like to come fully erect at the groin or hip joint. This move is critical for getting up from a low toilet seat, a chair seat, or a low car to the ground. Scoot to the front of the chair seat. Place your feet slightly behind your knees. Rest your hands lightly on the chair’s arms.

Keep your torso long and erect. In one movement, hinge, bend, or fold at the groin. Allow your face to look down at the floor just in front of your feet and continue to look in this direction until you have fully cleared the buttocks or pelvis from the chair seat. Feel how the forward momentum of hinging at the groin or hip joint allows you to push, push, and push the center of your heels down into the floor. Remember, let your pelvis or buttocks lift out of the chair first BEFORE you try to lift your head and torso.

Once out of the chair, let the pubic area of the pelvis continue to move forward to support the ‘unhinging’ of the groin or hip joint. Feel the downward pressure across the center of the foot, let the toes be light, and release any ‘gripping or clenching.’ Reverse the movement when lowering yourself down in the chair, letting the pelvis move or reach for the chair seat as you look down at the feet, knees, AND ankles bending, feeling the downward pressure into the center of the heels, lower the pelvis gently into the chair seat for a soft landing. No plopping.

Pause for 15-20 seconds before starting the process again. Repeat Center Heel Presses 4-5 repetitions several times a day to inhibit the chronic contraction of the psoas muscles and facilitate the muscles that oppose tight Psoas and return it to a length that promotes stability, balance, and quality movement.

Pelvic Runner’s Stretch:

To improve the tightness across the lower back at the waist level or vertically along one side of your lower spine when you walk or after a run, try this ‘tweak’ to the familiar runner’s stretch position:

Face a wall. Place your forearms on the wall, supporting your upper body weight, and position your feet in a step or stride position. The front leg is bent at the hip, knee, and ankle and placed about 5 inches from the wall. The back leg is extended with the bend only at the ankle, and the back leg’s heel is ON THE GROUND. Look a little down the wall towards the floor.

Here is the ‘tweak’: allow the pelvis to retract back and turn towards the extended or back leg. Stay there at the end of the movement for a few seconds. You will notice a lot of movement at the ankle joint as the extended leg bones rotate because of the moving pelvis. Be mindful of the forearms on the wall. One forearm may press more into the wall, perhaps the side of the extended leg. That is natural, but there is no reason to lift the forearm or elbow away from the wall. Allow the knee of the front leg to maintain a forward position, not allowing the knee to drift across the imaginary midline between the two legs.

Reverse the movement, allowing the pelvis to turn back toward the wall, allowing the forearm of the forward leg to press into the wall and assist the pelvis return to the starting position. Pause a few seconds before repeating the movement for 4-5 repetitions.

When we learn that it is the nervous system that is tightening muscles, we learn that we can consciously become influencers of a system that previously we thought was out of our control or that we could only be passive bystanders as we struggle to understand why our muscles are always so tight and why our body feels like it is slowly falling apart.

Eventually, knowing how the nervous system works transforms into a pearl of wisdom. We begin to change what we thought we could never change. We begin to move in ways we thought we could never move again. We begin to feel the joy that free, spontaneous movement unconsciously renders. We ultimately increase our potential to better care for ourselves as we age and move across our lifespan.

If pain, fear of pain, or chronic tightness persists, don’t ignore your body’s signals and wait until it interferes with your everyday activities. You should seek professional help. You can contact Montgomery Somatics to book an online session so that we can determine the best treatment choice and movement options for you.